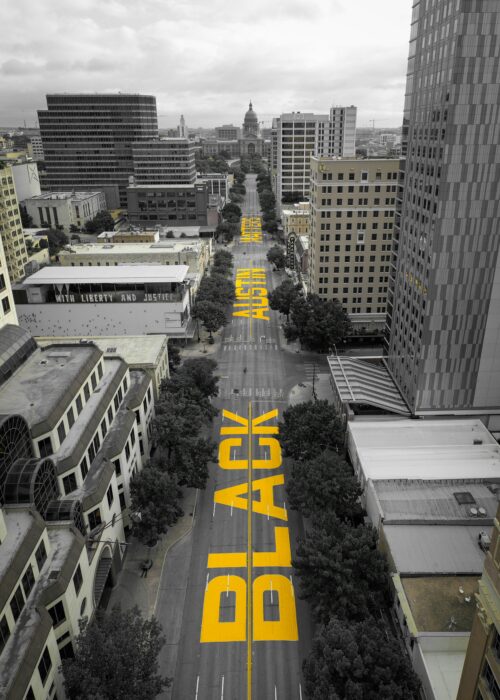

Black history is Austin’s history. Here are some ways to participate in, learn, enjoy and educate yourself on Black History this month. Learn more about Austin’s Black-owned businesses and organizations that deserve our love and support year-round. Let’s dive into Austin’s Black history and find out where you can celebrate and support Blackness today. (Cover photo by Ryan Magsino on Unsplash)

Celebrations and Events

Black History Walk Downtown

People of color have played a critical role in the city’s development since the 1820s. Join Black Austin Tours to hear from master storyteller Dr. Javier Wallace and discover the influence and presence of Black people in Downtown Austin. On his tour, you’ll explore centuries of contributions, history, and stories seldom told and will discuss the Black organizations and businesses that once thrived. The walk is one mile and educates guests on the history of Black people in Austin and their continued influence.

ULI Breakfast – Building an Inclusive Austin: Retaining Our Black Community

Austin’s rapid growth brings to the forefront crucial questions about its decline of Black and African American populations and what actions need to be taken to combat this decline. Delve into this essential dialogue through an engaging fishbowl conversation format at the February ULI Austin Breakfast on February 14. The discussion will revolve around the significant influence of Black-owned businesses, festivals, conferences and cultural events as key drivers of growth and unity. The panel features our Chief Impact Officer, Jenell Moffett.

Black Girls Don’t Wear Red Lipstick

We are so incredibly proud of Leta Harrison, our project manager. She is the first black woman photographer featured on the Austin Public Library’s gallery walls. Her show, Black Girls Don’t Wear Red Lipstick, opens on February 15 and runs until April 21.

Black in Tech Summit

Black leaders, entrepreneurs, investors and tech allies committed to diversity and inclusion should head to Capital Factory on February 15 for the 6th Annual Black in Tech Summit. Enjoy brunch, networking, a keynote speaker, mentoring, happy hour, insightful discussions and more.

Black History Celebration at Central Library

Tune into Austin PBS

Support Black-Owned Businesses and Organizations

Austin African American Leadership Institute

Austin’s Black History: Important Spaces

Hamilton Square

Hamilton Square is notable as the original home to Wesley Chapel, the first African-American church in Austin. It was formed at the corner of Congress and 5th Street in March 1865 by freed slaves after the Civil War. Before emancipation, enslaved people worshipped at First Methodist.

A few years later, they were able to build a church, Wesley on the Hill at the corner of 9th Street and Neches, overlooking Hamilton Square. The church thrived and remained at this location until 1928 when the property was purchased by the Austin School District. Wesley on the Hill relocated to East Austin, where the church remains today now known as Wesley Methodist.

Wooldridge Square

Three of Austin’s first churches were built overlooking Wooldridge Square, and the African-American churches that originated in the square continue in East Austin today.

One original church was the First (Colored) Baptist Church in 1839. The church was established by Reverend Jacob Fontaine, along with several other churches in the region. He was a pivotable person in shaping Austin as we know it today.

Fontaine and his congregation were strong educational advocates. He encouraged Black voters to support the establishment of the University of Texas even though the Black community would not be permitted to attend classes there until 1956. The voters understood the importance of education in freedom and equality. The congregation is cited as one of the strongest advocates for the education of freed slaves after the Civil War to combat their 95% illiteracy rate. The church moved to Hamilton Square in 1969.

Another crucial religious organization to Black education was the African Methodist Episcopal Texas Conference. In 1872, they founded the Connectional School for the Education of Negro Youth in Texas with the goal to train clergymen and teachers for Black schools and churches and give newly freed people the opportunity to have an education and be successful. The Connectional School moved to Waco after five years in Austin in hopes of reaching a larger Black community.

After 70 years of functioning as a home to three churches and a landfill, Wooldridge Square was re-engaged as a public space thanks to its lot neighbor, Mayor Wooldridge. The square was cleaned up and gained a new bandstand for public engagement. One of the most well-known of those engagements was Booker T. Washington himself in late September of 1911. He spoke to 5,000 of the then-current population of 30,000 on a stop of his Tour of Texas.

The square maintained its designation for public engagement through the years. During the 1960s, several civil rights marches ended at Wooldridge to end with a speech on that iconic bandstand.

Brush Square

Originally used for cotton and merchandise storage during the Civil War, Brush Square became the home of Austin’s Cowboy Culture. Texas cowboys were African-American, Mexican, and Anglo becoming one of the first lifestyles that actively brought together people of different races and cultures for a common purpose in the US.

Travis County Courthouse

Travis County Courthouse was the stage for Sweatt v Painter in 1950. This landmark case opened enrollment in the University of Texas Law School to Black students after the court ruled in favor of Heman Sweatt.

Sweatt applied for Law School in 1946 and was rejected because of his race. After Sweatt went to the state court to demand the University of Texas admit him, they quickly created “separate but equal facilities” called Law School for Negroes the next year and inequalities were obvious in school before it even opened. There was a lack of faculty, library resources, opportunities, prestige and cirriculum options.

The Court ruled unanimously that admissions violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and required Sweatt be immediately admitted to the University. This case helped lead to desegregation in public schools by setting a precedent for Brown V Broad of Education four years later.

Texas Union Ballroom

Dr. Martin Luther King Junior himself visited the Texas Union Ballroom to speak on the history of race relations in our country and implore local, state, and federal governments to work with the people to fight against and end segregation in 1962.

Pease Park

Pease Park has a darker history as the plantation of former Governor E.M. Pease. Ironically, Pease was an avid supporter of the Union while also owning enslaved people. He became the civilian Governor of Texas during Reconstruction but resigned two years later after he found creating a middle ground between radical policies impossible. After this, he donated a portion of his land to the public and after much misuse, it became a park.

Austin’s History: Redlining the Map

African-Americans used to live all around Austin until the early 1900s. There were 13 freedmen communities, including Clarksville, Wheatville, Pleasant Hill, Kincheonville, and Masontown. In 1928, a plan proposed by city contractor, Koch and Fowler created a “Negro District”. The plan was enacted by the city and cut off access to public services, school and other resources to African-Americans living in any other area of the city, forcing them to move east.

These segregation policies were reinforced by the New Deal program put forth by the federal government in 1935. The New Deal was put in place to assist with wealth recovery during the Great Depression, but the program did not include or benefit minorities. In fact, it even went a step further and promoted redlining. Redlined districts were not allowed to receive government-supported mortgages from the New Deal, excluding most of the minority neighborhoods in the nation. This included Austin’s previously redlined “Negro District” creating not only a geographic barrier but an economic barrier to people of color preventing them from financial recovery and establishing future generational wealth.

Then, in the 1950s, I-35 was erected right over one of the redlines, displacing several Black homes and businesses and taking out several green spaces never to be replaced. A community space for the Black and Hispanic populations, East Avenue, was destroyed as a physical and socio-economic barrier was placed between East Austin and downtown. This increased the negative impact of lack of zoning policies, public services and transportation for communities of color.

The Effects of Redlining Today

According to the Austin-American Stateman, a majority of our city’s people of color remain on the east side of I-35 to this day. And long-term effects of redlining are still evident in the lack of resources, ineffective public policies, and increased crime rates.

Dislocation is also still an issue to this day as discussed by Our Future 35. “For the past three decades, the once predominantly Black and Brown communities have been rapidly gentrified, sending home prices and taxes sky-high. Those dynamics again forced the removal of African-Americans and Latinos from their once very homelands to far-flung areas of Austin or to Pflugerville, Buda, Cedar Park and Round Rock.” You can also learn more about this issue from this study done at UT, Those Who Stayed.

I-35 is still such a symbol of division, that Black Lives Matters activists marched down the highway, shutting it down on multiple occasions during racial injustice protests in 2020.

There is an opportunity for change laid out on our I-35 Cap and Stitch page. “As TxDOT considers changes to this major north-south thoroughfare that has divided our community for decades, the Downtown Austin Alliance and the City of Austin have partnered with a diverse group of Austin leaders to co-create a shared vision that builds on this investment to ensure the best outcomes for all Austinites. By transforming I-35 through the heart of our city, we can invest in our community, improve all forms of transportation and create community parks, bridges and other amenities where the highway stands now.” Read more about the proposal we put forward in Current Projects.

Source Links

Downtown Austin Alliance – Current Projects: I-35

The Austin American Statesmen on Redlining